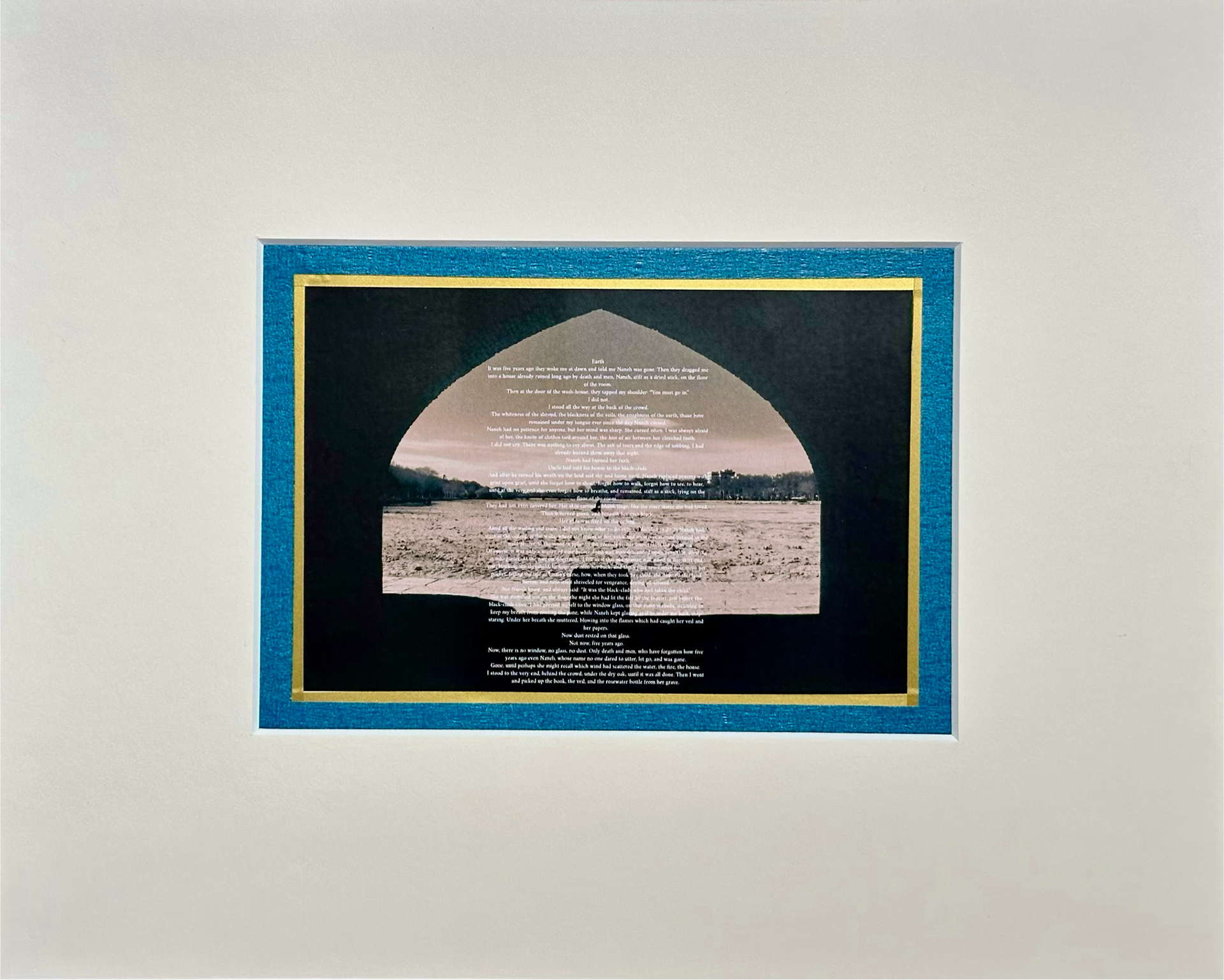

Bayat-e Esfahan, 2025

photo text installation

6 frames, each 20x30 cm

photo text installation

6 frames, each 20x30 cm

The installation Bayat-e Esfahan consists of six photos with six fictional fragments on each one, captured and written in the past ten years in and about the city of Esfahan, its multilayer history, conservative and traditional culture, and its contemporary tragedy, the complete drought of Zayandeh Rud, the largest river of the Iranian plateau.

The photos are printed in a small size, 10x15 cm, imitating the traditional small size of Persian paintings, framed in large passepartouts, as seen in museums, and presented with a magnifier that helps to read the story. This work serves not only as a witness but also as a requiem for a dead river that was named after life.

The story (originally written in Persian, translated and edited in English) goes back and forth between oral stories, dreams, and reality. It consists of six fragments: Water, Rice, Wind, Fire, Cypress, and Earth. Though each fragment is independent, all of them revolve around a single figure, Naneh, an old woman who reflects different moments in the history of a village.

The installation was exhibited as part of the Long Night of Images in Motavali Expanded [4] curated by AmirAli Ghasemi at Villa Kuriosum in Berlin.

Bayat-e Esfahan

Water

“The call to prayer had already passed. It was exactly seven in the morning, when the sun began its struggle but could not overcome the darkness of the clouds, that Imma stepped out of the house with the first flock of crows.”

That’s how Naneh always told it.

“On Fridays in those days, not even a dog left the house. But for Imma, it was a ritual. Every Friday, just after the cockcrow, she would set out. She leaned against the tree, as it rumbled its first snores, and whispered something into its branches. When Haj-Baba gathered the children, sometimes with force, sometimes with beatings, I was still the girl of the house. He would make us memorize Imma’s chants.”

At that point, she would always pause, remembering Haj-Baba. She could go on about him: how each day someone from the upper or lower quarter of Dey would come for divination, and Haj-Baba forbade it, yet reluctantly took up the rosary at their insistence. Then she would continue, weaving story into story, until she reached those years again, pressing her hand to her heart, swallowing her words.

“Nothing else happened. Imma circled around a few houses, then climbed the hillside. The smell of rain had scattered across the trees’ reddened astonishment. She drew a deep breath, a shiver running from the distant mountains straight into the back of her eyes. On the slope of the opposite hill, beneath the sudden-lashing rain, a small group dressed in black carried a coffin on their shoulders. She saw it herself. No one in Dey had ever seen such figures before. If anyone claimed to, it was only in the towns, and even then, no one believed them, or said it was just a rumor passed along. No one knew what black-clads really looked like. Even those who had seen them could never give a description that lasted beyond the month. But that day, there were five. Two at the front, two at the back, bearing the coffin. One walked alongside, shifting the rope on his shoulder, glancing about.

At the top of the hill stood the old oak, waiting. In this season, in this rain, at this time of day, neither tree nor soil nor even God had patience for a dead. And so, when the five reached the summit with the coffin, she went to the edge, looking down into the valley, just to be sure the river was still there.”

Naneh repeated this often, so that we would never forget that the river remained. Sometimes she explained:

“No matter how hard it rushed, it always stayed, pooling at the foot of the cliffs, at the bottom of the valley. Two things don’t belong to this place or its people, and never did: the oak, whose name and endurance testified to generations seen and unseen; and the river, which had been there from the beginning. Later, when they channeled it into canals, it was only so the winter floods wouldn’t wash away their lives. Haj-Baba used to say: Who knows how many have drowned in those canals alone.”

Then she would remember again:

“The black-clads dropped the box. They looked around. Sat down. Dug into the wet cemetery soil with clawed hands.”

By now, surely, Naneh knew each of them by name.

“All the while, the old oak stared, and apart from the clouds, no one mourned. They worked until the grave was deep enough that the lash of rain would not carry away the corpse. It was no place to die, under such a storm. She shivered, turned, and made for the river. She knew that in those moments a shrouded body slid into the grave, cold, wet earth thrown over it in unmarked silence, while the black-clads vanished beyond the hill.”

If you asked then whether it had been Haj-Baba or someone else who witnessed this, she would fall silent, glance aside, then say:

“All at once, a gunshot rang through the valley. One creature chased another through the forest. It was clear the next corpse would sleep beside the fire.” She cursed.

“The river had risen. Near the stones, one could still see it, then for a few days they would glimpse its shifting colors, but in the middle current, the river turned from blue to green to black, and was gone.

She unbuttoned her vest. Stripped off her skirt, tied it to a heavy rock. She whispered something to the stone. Stepped into the waves. Her teeth rattled against each other, but she went further. Her hands had grown numb. The weight almost slipped from her forearms, down into the unseen depths. The water surged up to her chest. She gasped, pushed forward. The stone floated lighter in the current. The rain granted no mercy. The sun had wholly surrendered to the blackness.

A young disappeared beneath the oak.

A lifeless boar lay fallen beside a newborn’s fire.

The old tree pulled at its roots, humming a lullaby.

A lifeless boar lay fallen beside a newborn’s fire.

The old tree pulled at its roots, humming a lullaby.

And the stone, wrapped in the skirt, indifferent to the roar of the waves, drifted gently down, down, into the depths of blue, then green, then black, and was gone, just like Imma’s young beneath the soil.”

Rice

The smell of young wheat stalks, or the damp steam of husked rice, or the thickness of the afternoon sun, it was all the same. Even if one looked hard, nothing strange could be found here. Not even after a century had passed.

But my heart was restless as a revolution.

Naneh’s eyes would not leave me, eyes that pleaded, that swore by everything sacred. I knew she hadn’t shut them at all the night before. Since morning, she had been sullen, though she never said which poor soul had haunted her sleep, leaving her trembling and dripping all over.

I grew weary of it. I stayed neither hidden nor uncovered, neither here nor there, I just walked out. No patience left. I reached the end of the alley, turned back, and headed the other way. Skirted the cattle yard, pushed through the alleys one by one, until I found myself out in the open plain. And still Naneh’s eyes would not leave me.

A blue pickup came from afar, stacked high, bursting with sacks of carrots. It honked: “God give you strength!” And as it rolled off through the dust and mire, my hand rose halfway in reply, then fell again. When I cast my gaze properly, I found myself turning into the greenhouse road.

On a bent, crooked piece of cardboard someone had scrawled: woodfired.

A little further on, men and women sat crouched, bundles and empty sacks in their hands, waiting by the bakery. The black veils of the women and the masks of the men seemed to let no dust pass. One by one, they raised their heads, staring at me as I watched the fire’s heat in the oven. Even the smell of the burning logs was the same, and I was certain that in another hour the scent of bread, sesame, and fenugreek would be the same too.

When another truck circled and pulled up to the bakery to unload armfuls of wood, I came to and lost my staring eyes, turned back to the road. Passed two bakeries, each with their signs: woodfired.

At last, I reached the rusted, battered door of uncle’s house. At first I meant to pass, but stopped, drew my fist, and slammed it against the door. All four wood-pillars of the frame shook. Then its shout, tangled in the bleating of sheep, was swallowed in the roar of another pickup that sped off, lifting clouds of dust into the sky.

I waited until it was gone. In silence, I pressed my ear against the door and sharpened my eyes. Ants scrambled in a panic over the dirt, but of uncle there was no trace. How many days has it been? I clenched my hand again and struck harder. Nothing. Silence.

I lingered there a few minutes, standing at the door, stomping ants, and thinking of Naneh, her lips twisting and trembling. Then I walked on toward the cropland.

Old men were astride their Chinese bicycles, mud caked up from knees to calves, splashing back into the wheel spokes as the wind carried it off. Evening was falling. Every day, one new cropland turned to a wetland. I passed Haji’s, turned, and went as far as the well. The motor was coughing and sputtering, the water as if cursing our ancestors.

I pressed on along the borders, brushing aside the rows of oleaster trees and chamomile flowers, until I reached the land. The Afghans who had finished the work were packing up their things off the ground, and before leaving, they fixed me with their gaze, sharp and searching. “God give you strength!”

I squatted at the land, reached into the mud. Naneh’s eyes were still fresh, framed inside my head. Quivering.

I kicked off my shoes, rolled up my trousers, stepped into the mud. The sun was sinking to the dovecote. Someone, somewhere, was digging with a spade. Water gurgled into the furrows, the motor sputtered once more, then fell silent. And all went quiet. Empty.

No one. The mosquitoes hadn’t even found their way there yet.

I went deeper into the land. Stomped my foot. Good and muddy. I twisted my heel, the muck sucked me in to the ankles.

And still, in my ears, Naneh kept swearing me away from the land.

Wind

The sound of death was like the voice of Abdul Basit reciting Surah al-Qadr, when at last they pulled that young man, half-eaten by fish and tangled in river weeds, out of the water after so long a wait. That day too, it rained. The wind gave no respite. It slapped water against people’s faces, dragged branches into the clouds, lashed earth and homes alike.

Men and women dressed in black. In those days, one wore black only for the dead. On foot, they made their way to the graveyard, all mud and mire, except for scattered stones, black, white, gray, that jutted up here and there like watchful heads, rising to see who had come. Those without stones carried a scrap of wood inscribed with a name, so they would not be lost amid the rest.

His mother, the mother of that half-eaten youth, had not permitted an autopsy. When I asked what autopsy meant, they said: dissection. Like when at school we had cut open a fish. I had gagged, the teacher had laughed, and that night I dreamt a fish was laughing inside my stomach, while the children waited with scalpels to split me open. I had not let them.

They told everyone he had gone to swim in Ghorugh and drowned. I, a child of barely a handspan, asked where Ghorugh was. This time, no one answered. Later, once, I went myself. It wasn’t like the hillside. The river was wild, thick with thin trees and damp earth, it stretched as far as the eye could see into waves upon waves of water, bottomless. I was afraid. I didn’t want to return. I never did. I never knew how to swim anyway. Even if I had, I would not have entered.

Uncle said the boy was his friend. That he had been there when they pulled him from the water, had seen his blue body, his eyes bulging as if they would burst from their sockets, staring. His half-eaten muscles stiffened, veins swollen with water, clothes plastered with weeds, just like the fish we had carved open at school. But uncle had never had a friend, never even exchanged greetings with others. Perhaps he wasn’t there at all. Yet I had seen him that day, suddenly wrench himself up, leap onto the motorbike, tear out of the house without shutting the door behind. And he did not return until they brought back the corpse. Then he came, cloaked in black.

The drums beat. Lightning split the sky, but thunder lost its sting. I remember it well: the sky was narrow, the wind had broken clay houses and croplands apart.

I asked: “Has Muharram come?”

Naneh said: “When a young one dies, they beat the drums.”

Naneh said: “When a young one dies, they beat the drums.”

I thought, Imam Husayn had not been young. But I said nothing, because Naneh had drawn her veil tight over her head and stepped away from the veranda as the drumming drew near.

They said the mother had endured much, waiting, resisting. She hadn’t let them cut him further into pieces.

Just like me, in my dream.

To everyone she said: “He drowned while swimming in Ghorugh.”

In those days, the young often went there to swim together. Sometimes stories circulated of how one had been caught in the current, sapped of strength, until the others rushed in, pulling him back in time.

Why hadn’t he been saved?

That thought still lingered when I heard a woman say: “With this rabid river, when did you ever see anyone go alone to Ghorugh to swim?”

Fire

I want to seize the light in my fist. But it slips, spills into the night.

It had been some days since their coming, maybe ten days and ten nights, when men and women settled at the bottom of the riverbed. Then one among us rose, set his head aflame, and ran.

The valleys had vowed themselves to the wind. The trees swayed like mourners as people moved back and forth, watching the fire rise into the night air. Some said: “It is a miracle.” “The Promised One has come.” “Another god sits upon the earth.”

But we knew it was no apparition. The one flying with the fire was a body of our own. And it was not the wind, but the wailing of women, that shook the trees.

The black-clads came swiftly, tearing strips from his shirt, tying them knot by knot to window grates, whispering in the crowd, burying papers and signs beneath the soil, the same soil we put into our mouths to soothe our parched screams.

That night, light filled the sky entire.

Naneh said: “It is the end of time.”

But again the minaret called to prayer. Dawn broke. We remained atop hills that even the wind had passed by.

Afterward, men emerged from behind the trees, a flood of black pouring down into the valley.

I said: “How can one carry ash upon the hands?”

Naneh said: “One way or another, something must be done.”

I said: “How can one carry ash upon the hands?”

Naneh said: “One way or another, something must be done.”

Then she whispered repentance, breathed blessings, or some other chant, then blew.

But there was no wind to carry the words.

The prayers fell onto the soil instead. Soil now scattered with talisman bodies and scraps of scorched cloth.

But there was no wind to carry the words.

The prayers fell onto the soil instead. Soil now scattered with talisman bodies and scraps of scorched cloth.

I said: “Let’s go back.”

She said: “Deserves mercy.”

I asked: he, or us? But only to myself.

She said: “Deserves mercy.”

I asked: he, or us? But only to myself.

Naneh had long since put aside her veil, saying it reeked of blood and smoke. But that day, she knotted a strip of black cloth around her body.

I asked: “So you will not join the black-clads?”

She fixed her sharp gaze on my chest and set out into the dry riverbed.

She fixed her sharp gaze on my chest and set out into the dry riverbed.

It felt like a desert, stretched between two valleys.

“May the wind not rise again, for it will scatter what is left of our eyes, everywhere.” She said it mid-journey, piercing the silence with fury.

“May the wind not rise again, for it will scatter what is left of our eyes, everywhere.” She said it mid-journey, piercing the silence with fury.

I followed two steps behind, still tangled in thought, thinking of the night and the fire, and my blood burned against itself, certain that once again the old oak was surrounded.

Naneh sat on the cracked earth, clawing at the fissures where the ground had split open, whispering water, water. Out from the cracks, scraps of paper protruded. She clawed at them, blew on them.

I reached out, she struck my hand away, whispering repentance under her breath, eyes blazing at me.

She spread the corner of her black cloth upon the dry bed of the river, now home to no water, and gathered onto it handfuls of prayers, dried sludge, broken clods of earth. She muttered again, but the only sound that carried was a faint whistle.

She knotted the bundle. Pulled herself up, carrying the heavy bundle against her trembling bones.

Lagging behind me, she said: “We must kindle another fire.”

Cypress

I picked up the strip of black cloth from atop the grave. Three times, I tapped my fingertip against the white stone, then tucked the twenty-liter water can beneath my arm and set off for the canal. I filled the can at the spout by the canal, circled the shrine, and returned to see Haji’s son standing at a distance, staring at the cypress like a minaret. Just last week, Thursday, the same day I had planted the cypress at the head of Naneh’s grave. The shovel was still leaning by the tree. Naneh’s grave, right next to Haji’s; it’s been over a year they’ve lain side by side. I’d never seen Haji outside the graveyard, not even in life, he’d stand by the shrine with a few other shadows, staring out empty and silent, exactly as his son now looks at the cypress.

A kid pushed a rickety bicycle between the graves, huffing, throwing sideways glances at the man. As he passed me, he muttered, “Don’t talk to the black-clad ones.” He grinned under his breath, then bolted off and got lost in the jumble of children across the canal. The scent of earth and rosewater sharpened my breath. Sunlight scattered over the stones as if waiting for the dead to grow green. Of all the white, grey, and black gravestones, only the cypress was new and stood green and upright. Eye to eye with the man.

I tipped the can, poured half at the foot of the cypress, half onto Naneh’s stone.

It was just last week. I stood just here, just here, where now I stare, stunned at the cypress toppled onto Naneh’s grave. Its roots, torn and dangling, hanging in the air. Haji’s son leans against the shovel, stuck above Naneh’s head, just where the cypress was and is no longer. The sun drifted in and out of the clouds. The son-in-law, brother-in-law, and Haji’s brother stood off, gazing into emptiness at the grave. I dropped the can. I stepped up and pulled the mute, slender trunk off Naneh’s stone. My eyes burned. Fire rose in my chest, as if clutching the root of my throat so its smoke wouldn't fill every end of the graveyard.

“God give you strength!” Haji’s brother stepped forward. Naneh had no patience for their talk, and neither did I; if I did, the words would be crushed between my fist and their teeth. Poor words. Haji’s son shifted his bulk along the shovel. I picked up the can and let a last drop of water fall on Naneh’s stone.

“Your Naneh is not content with this cypress here, either.” Again, the old man opened his mouth. If Naneh had her way, she'd barely let your gaze fall on her grave. I said nothing. I sat, knees drawn up, back to Haji’s grave. The son-in-law and brother-in-law kept their blank stares. His son’s head was tucked into his forearms on the shovel.

“It was just last Thursday night, just before the dawn call, Haji came to me in a dream.” May the grave be home for all your sleep and waking. I said nothing.

“He said, uproot this cypress. Even when he was alive, Haji’s word was the truth. May light fall on his grave.” He fears, perhaps, that the cypress shadow will block the light’s descent.

Haji’s son tucked the shovel under his arm. His son-in-law and brother-in-law slipped their hands under the speechless trunk and lifted it. I watched the roots, torn and dangling away in midair.

“Haji said, when they water this cypress, I feel cold in my grave.”

Earth

It was five years ago they woke me at dawn and told me Naneh was gone. Then they dragged me into a house already ruined long ago by death and men, Naneh, stiff as a dried stick, on the floor of the room.

Then at the door of the wash-house, they tapped my shoulder: “You must go in.”

I did not.

I stood all the way at the back of the crowd.

I did not.

I stood all the way at the back of the crowd.

The whiteness of the shroud, the blackness of the veils, the roughness of the earth, those have remained under my tongue ever since the day Naneh cursed.

Naneh had no patience for anyone, but her mind was sharp. She cursed often. I was always afraid of her, the knots of clothes tied around her, the hiss of air between her clenched teeth.

I did not cry. There was nothing to cry about. The salt of tears and the edge of sobbing, I had already burned them away that night.

Naneh had burned her faith.

Uncle had sold his honor to the black-clads.

And after he turned his wrath on the land and sky and home itself, Naneh replaced prayers with grief upon grief, until she forgot how to shout, forgot how to walk, forgot how to see, to hear, until at the very end she even forgot how to breathe, and remained, stiff as a stick, lying on the floor of the room.

Naneh had burned her faith.

Uncle had sold his honor to the black-clads.

And after he turned his wrath on the land and sky and home itself, Naneh replaced prayers with grief upon grief, until she forgot how to shout, forgot how to walk, forgot how to see, to hear, until at the very end she even forgot how to breathe, and remained, stiff as a stick, lying on the floor of the room.

They had not even covered her. Her skin carried a bluish tinge, like the river water she had loved.

Then it turned green, and beneath her eyes black.

Her gaze was fixed on the ceiling.

Then it turned green, and beneath her eyes black.

Her gaze was fixed on the ceiling.

Amid all the wailing and tears, I did not know what to do either. I decided to do as Naneh had, stare at the ceiling, at the walls, where still traces of her voice and its waves seemed pressed in the mud-plaster, at the wooden pillar in the veranda visible from inside the room.

Of course, it was only a matter of time before death and men descended upon even that, dividing it into pieces. At the narrow doorframe, I felt as if that old woman still stood in her skirt and vest, blocking the threshold, to hoist me onto her back, and slip a pink ten-toman note from her pocket, telling the tale of Imma’s curse, how, when they took her child, she damned this land barren, and time itself shriveled for vengeance, drying all around.

But Naneh knew, and always said: “It was the black-clads who had taken the child.”

She was stretched out on the floor the night she had lit the fire by the brazier, just before the black-clads came. I had pressed myself to the window glass, on that same veranda, straining to keep my breath from misting the pane, while Naneh kept glaring as if to order me back, stop staring. Under her breath she muttered, blowing into the flames which had caught her veil and her papers.

Now dust rested on that glass.

Not now, five years ago.

Not now, five years ago.

Now, there is no window, no glass, no dust. Only death and men, who have forgotten how five years ago even Naneh, whose name no one dared to utter, let go, and was gone.

Gone, until perhaps she might recall which wind had scattered the water, the fire, the house.

I stood to the very end, behind the crowd, under the dry oak, until it was all done. Then I went and picked up the book, the veil, and the rosewater bottle from her grave.